On embodied cognition

A note on limitations of Classic Model of Cognition that embodied cognition hopes to answer

Embodied cognition

Embodied cognition

Limitations of Classic Model of Cognition that embodied cognition addresses

Traditionally, cognitive science has viewed the mind as an abstract information processor, whose connections to the outside world were of little theoretical importance. Perceptual and motor systems, were thought to serve merely as peripheral input and output devices, and were not considered relevant to understanding “central” cognitive processes.

The Computational Theory of Mind combines an account of reasoning with an account of the mental states. This is the thesis that intentional states such as beliefs and desires (propositional attitudes) are relations between a thinker and symbolic representations of the states. These representations have both semantic and syntactic properties and reasoning is responsive only to the syntax of the symbols–is known as ‘formal symbol manipulation’. One such system of rules that may be used is propositional logic.

For example, to believe that there is a dog on the rug is a particular functional relation (characteristic of the attitude is that of belief) to a symbolic mental representation whose semantic value is “there is a dog on the rug”; Similarly, to hope that there is a dog on the rug is a different functional relation (characteristic of the attitude of hoping) to a symbolic mental representation with the same semantic value. Two of the most cited classical approaches are Fodor’s, ‘Language of thought(LoT)’, and Marr’s, “Three Levels”.

The language of thought hypothesis (LoTH) proposes that thinking occurs in a mental language. Often called Mentalese, the mental language resembles spoken language in several key respects: it contains words that can combine into sentences; the words and sentences are meaningful; and each sentence’s meaning depends in a systematic way upon the meanings of its component words and the way those words are combined. It claims that Mentalese contains analogues to the familiar logical connectives (and, or, not, if-then, some, all, the). Iterative application of logical connectives generates complex expressions from simpler expressions. However, it has a very limited scope concerning only propositional attitudes and the mental processes in which they figure, such as deductive inference, reasoning, decision-making, and planning. It does not address perception, motor control, imagination, dreaming, pattern recognition, linguistic processing, or any other mental activity distinct from high-level cognition.

Marr’s three levels of analysis promotes the idea that complex systems such as the brain, a computer or human behaviour should be understood at different levels. Marr’s three levels are:

-

Computational At this level we describe and specify the problems we are faced with in a generic manner, but do not say how these problems are to be solved.

-

Algorithmic This level forms a bridge between the computational and implementational levels, describing how the identified computational problems can be solved.

-

Implementational The mechanism, and its organisation, in which computation is performed. This is biological like neurons and synapses.

Limitations to Classical approach:

- Does syntax explain semantics?

Putnam (1980) pointed out a major obstacle to such a view. It stems from a consequence of the Lowenheim-Skolem theorem in logic, from which it follows that every formal symbol system has at least one interpretation in number theory. This being the case, take any syntactic description D of Mentalese. Because our thoughts are not just about numbers, a canonical interpretation of the semantics of Mentalese (call it S) would need to map at least some of the referring terms onto non-mathematical objects. However, Lowenheim-Skolem assures that there is at least one interpretation S* that maps all of the referring terms onto only mathematical objects. S* cannot be the canonical interpretation, but there is nothing in the syntax of Mentalese to explain why S is the correct interpretation and S* is not. Therefore syntax underdetermines semantics. *

- Are all of our cognitive abilities formalizable and computable?

The oldest argument is due to J.R. Lucas (1961), who has argued that Gödel’s incompleteness theorem poses problems for the view that the mind is a computer. A distinct line of argument was developed by Hubert Dreyfus (1972). Dreyfus argued that most human knowledge and competence – particularly expert knowledge – cannot in fact be reduced to an algorithmic procedure, and hence is not computable in the relevant technical sense. The novice chess player might follow rules like “on the first move, advance the King’s pawn two spaces”, “seek to control the center”, and so on. But following such rules is precisely the mark of the novice. The chess master simply “sees” the “right move”. There at least seems to be no rule-following involved, but merely a skilled activity.

- Is computation sufficient for understanding?

The most influential criticism of CTM has been John Searle’s (1980) thought experiment known as the “Chinese Room”. In this thought experiment, a human being is placed in the role of the CPU in a computer. He is placed inside of a room with no way of communicating with the outside except for symbolic communications that come in through a slot in the room. These are written in Chinese, and are meaningful inscriptions, albeit in a language he does not understand. His task is to produce meaningful and appropriate responses to the symbols he is handed in the form of Chinese inscriptions of his own, which he passes out of the box. In this task he is assisted by a rulebook, containing rules for what symbols to write down in response to particular input conditions. This set-up is designed to mimic in all respects the resources available to a digital computer: it can receive symbolic input and produce symbolic output, and it manipulates the symbols it receives on the basis of rules that are such that they can be applied on non-semantic information like syntax and symbol shape alone. The only difference in the thought experiment is that the “processing unit” applying these rules is a human being.

What does it mean to say that cognition encompasses the environment?

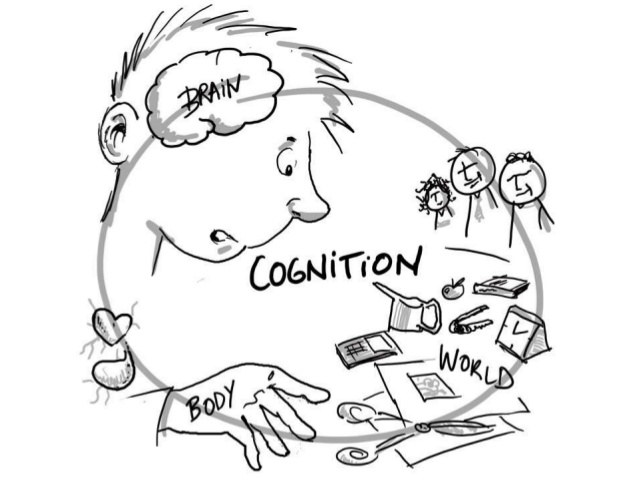

Enter the idea of embodied cognition. The emerging viewpoint of embodied cognition holds that cognitive processes are deeply rooted in the body’s interactions with the world. The belief is that our bodies and their perceptually guided motions through the world do much of the work required to achieve our goals, replacing the need for complex internal mental representations. This simple fact utterly changes our idea of what “cognition” involves, and thus embodiment is a completely different theory.

Embodied cognition encompasses the environment through some of the claims underlying the theory as presented below:-

- We off-load cognitive work onto the environment:

Because of limits on our information-processing abilities (e.g., limits on attention and working memory), we exploit the environment to reduce the cognitive workload. We make the environment hold or even manipulate information for us, and we harvest that information only on a need-to-know basis. Humans are not entirely helpless when confronting the representational bottleneck, and two types of strategies appear to be available when one is confronting on-line task demands. The first is to rely on preloaded representations acquired through prior learning. Consider the example of counting on one’s fingers. It can be done more subtly, differentiating the positions of the fingers only enough to allow the owner of the fingers to keep track. To the observer, this might look like mere twitching. Imagine, then, that we push the activity inward still further, allowing only the priming of motor programs but no overt movement. If this kind of mental activity can be employed successfully to assist a task such as counting, a new vista of cognitive strategies opens up.

What about novel stimuli and tasks, though? In these cases there is a second option, which is to reduce the cognitive workload by making use of the environment itself in strategic ways—leaving information out there in the world to be accessed as needed, rather than taking time to fully encode it. The environment can also be used as a long-term archive, as in the use of reference books, appointment calendars, and computer files. This can be thought of as off-loading to avoid memorizing, which is subtly but importantly different from off-loading to avoid encoding or holding active in short-term memory what is present in the immediate environment. Kirsh and Maglio (1994), as noted earlier, have reported a study involving the game Tetris, in which falling block shapes must be rotated and horizontally translated to fit as compactly as possible with the shapes that have already fallen. The decision of how to orient and place each block must be made before the block falls too far to allow the necessary movements. The data suggest that players use actual rotation and translation movements to simplify the problem to be solved, rather than mentally computing a solution and then executing it. Glenberg and Robertson (1999) have experimentally studied one such example, showing that in a compass-and-map task, subjects who were allowed to indexically link written instructions to objects in the environment during a learning phase performed better during a test phase than subjects who were not, both on comprehension of new written instructions and on performance of the actual task.

- The environment is part of the cognitive system: The information flow between mind and world is so dense and continuous that, for scientists studying the nature of cognitive activity, the mind alone is not a meaningful unit of analysis. The thesis of extended cognition is the claim that cognitive systems themselves extend beyond the boundary of the individual organism. On this view, features of an agent’s physical, social, and cultural environment can do more than distribute cognitive processing: they may well partially constitute that agent’s cognitive system.

Consider three cases of human problem-solving. Clark(1998)

- A person sits in front of a computer screen which displays images of various two-dimensional geometric shapes and is asked to answer questions concerning the potential fit of such shapes into depicted ‘sockets’. To assess fit, the person must mentally rotate the shapes to align them with the sockets.

- A person sits in front of a computer screen, but this time can choose either to physically rotate the image on the screen, by pressing a rotate button, or to mentally rotate the image as before. We can also suppose, not unrealistically, that some speed advantage accrues to the physical rotation operation.

- Sometime in the cyberpunk future, a person sits In front of a computer screen. This agent, however, has the benefit of a neural implant which can perform the rotation operation as fast as the computer in the previous example. The agent must still choose which internal resource to use the implant or the good old-fashioned mental rotation), as each resource makes different demands on attention and other concurrent brain activity.

How much cognition is present in these cases? We suggest that all three cases are similar. Case (3) with the neural implant seems clearly to be on a par with case (1). And case (2) with the rotation button displays the same sort of computational structure as case (3), distributed across agent and computer instead of internalized within the agent. If the rotation in case (3) is cognitive, by what right do we count case (2) as fundamentally different? We cannot simply point to the skin/skull boundary as justification, since the legitimacy of boundary is precisely at the issue.

Are problems with the idea of understanding cognition as extended across the environment?

The claim is this: The forces that drive cognitive activity do not reside solely inside the head of the individual, but instead are distributed across the individual and the situation as they interact. Therefore, to understand cognition we must study the situation and the situated cognizer together as a single, unified system.

The first part of this claim is trivially true. Causes of behavior are surely distributed across the mind plus environment. More problematic is the fact that causal control is distributed across the situation is not sufficient justification for the claim that we must study a distributed system. Science is not ultimately about explaining the causality of any particular event. For a set of things to be considered a system in the formal sense, these things must be not merely an aggregate, a collection of elements that stand in some relation to one another (spatial, temporal, or any other relation). From this description, though, it should be clear that how one defines the boundaries of a system is partly a matter of judgment and depends on the particular purposes of one’s analysis. Thus, the sun may not be part of the system when one considers the earth in biological terms, but it is most definitely part of the system when one considers the earth in terms of planetary movement.

The organization of a system —the functional relations among its elements, and indeed the constitutive elements themselves—would change every time the person moves to a new location or begins interacting with a different set of objects. That is, the system would retain its identity only so long as the situation and the person’s task orientation toward that situation did not change. Such a system would clearly be a facultative (temporary) system, and facultative systems like this would arise and disband rapidly and continuously during the daily life of the individual person.

The distributed view of cognition thus trades off the obligate (permanent) nature of the system in order to buy a system that is more or less closed.

If, on the other hand, we restrict the system to include only the cognitive architecture of the individual mind or brain, we are dealing with a single, persisting, obligate system. The various components of the system’s organization— perceptual mechanisms, attentional filters, working memory stores, and so on—retain their functional roles within that system across time. The system is undeniably open with respect to its environment, continuously receiving input that affects the system’s functioning and producing output that has consequences for the environment’s further impact on the system itself. Given this analysis, it seems clear that a strong view of distributed cognition—that a cognitive system cannot in principle be taken to comprise only an individual mind—will not hold up.