The case for Pessimism and the half empty glass

What would you choose to be and does it even matter?

which one to choose?

which one to choose?

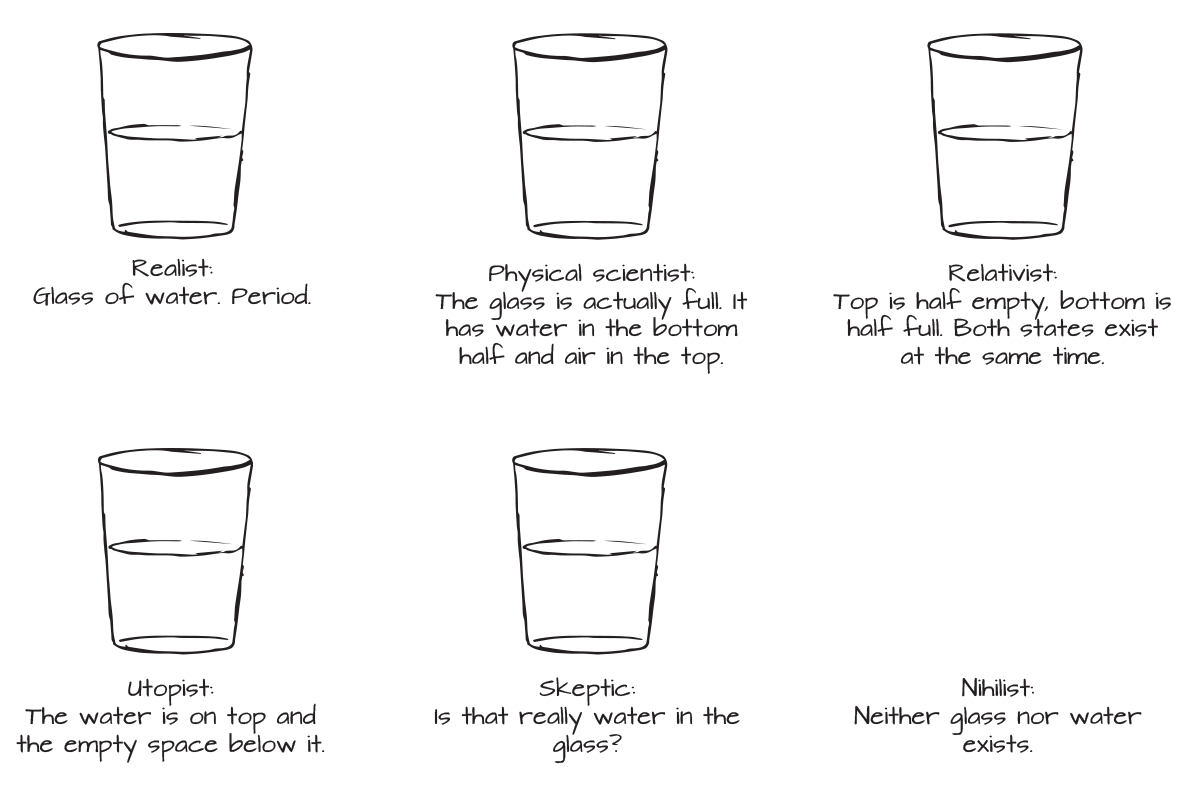

Scene 1: A glass with water in it. The water is at the half-way mark. Which leads to a critical question: Is the glass half empty? Or is the glass half full? What would you choose? Does it matter? After all, either of the above is true. Scene 2: You are lost in a desert, with a glass of water. The water is at the half-way mark. I urge you to go back to the same question. What would you choose now? Does it matter?

Chances are that you had a larger tendency to quantify the glass as half empty in the latter scene than the former. The objective truth remained, the glass contained water to the half-way mark. However, when we put our glass into context, something changed. A seemingly trivial binary decision turned out to have far-reaching implications. The truth itself doesn’t change, but how we interpret it can and may have a huge impact on our further actions. Seeing the glass as half full is archetypal of an optimist. She focuses on what is there, so much that can be done with the glass. On the contrary, the pessimist sees the glass as half empty. He sees that the glass used to be full, and soon he will feel the thirst. Woe is him.

In this time of crisis, all of us will soon have to psychologically tune ourselves to the “new normal” and the post-COVID world, if we haven’t already. One might argue, as is supported by conventional wisdom, that every crisis calls for a strategy of “optimism tempered with realism”; and intuitively “faith”, “belief” and “hope” along with other convenient abstracts make political, social and economical sense. However, there is a case to be made for the pessimists and the Eeyores of the world. Defensive pessimists, to be specific. Because when the world stops spinning, defensive pessimists will be the ones with their feet on Mars, metaphorically speaking.

Pessimism isn’t just about negative thinking, research has shown that it also includes a focus on outcomes – that is what you expect will happen in the future. While strategic optimists try to maintain a positive stance throughout, they might be prone to be guilty of fitting the events to a positive hypothesis instead of the hypothesis to the events. In the words of Julie Norem, a psychology professor at Wellesley College and a pioneer of the defensive pessimism theory, “trying to force positivity is a bad strategy for the truly anxious”.

When people are being defensively pessimistic, they set low expectations, but then they take the next step which is to think through in concrete and vivid ways what exactly might go wrong. To delve a little deeper into a defensive pessimists’ mind, imagine you have to speak publicly in front of an audience. You start feeling anxious about it and start contemplating the disaster. Maybe you will trip over while walking up the stage, or knock over the coffee mug onto your dress. The microphone will malfunction, and you’ll get questions from the audience you’ve never thought of. At the first instance it seems like you’re spiraling down a tar pit and catastrophizing. However, the way this differs from a garden-variety pessimism is the constructive adaptation, and the action to safeguard against some of these items on your checklist of disasters. Defensive pessimism may not help you get rid of your anxiety, but the flip side is that it keeps your mind anchored and focuses you on things you can control. It helps you direct your anxiety towards a productive activity. In some sense, you’ve peaked in anxiety before the actual performance.

Everything comes with caveats of its own, and in the case of pessimism, a social aspect is certainly something of interest. This tendency can severely affect relationships with people who fall in the more optimistic basket as constantly practicing it will label you as the harbinger of gloom. If you’re doing it out loud, other people tend not to like it. They tend to have questions about your competence. There’s this idea that there’s something wrong with you if all you see are problems in the world. Although it is okay for someone to just try to be happy, emotional states by definition are supposed to be transient. You’re going to be happy sometimes, and not happy sometimes. If your goal is to be happy, the next time you’re not happy, you’ll feel like you have failed. If you feel anxious and it feels real to you, ignoring it generally doesn’t work out.

Defensive pessimism, of course, is not for everyone. Those vulnerable to acute and frequent bouts of anxiety must not look for vindication in negative thinking. You are getting worked up in the process, it takes energy. If you’re doing it for everything, you’re more likely to wear yourself out. That said, anxiety is exhausting anyway. But, for a large number of us who keep bouncing between radically contrasting versions of emotional extrema, defensive pessimism provides a path that challenges the herd mentality who advocate positivity for the sheer sake of it.

One could argue that defensive pessimism is, at this moment, not just sensible but the need of the hour. When we heard of the lockdowns, all of us rushed to get the essential supplies stocked up on the eventuality of a shortage. Because we assumed the worst, we actually got off and did something about it. I think the real edge a defensive pessimist might have when the world reopens is that they will continue to take more precautions, and prepare for the roller coaster of peaks that may happen. They’re less likely to be caught off guard by any of it.

Defensive pessimism does not view the future through rose coloured glasses. It sees a post-pandemic planet not as a return to paradise but as a place that is still prone to pitfalls and prejudices, and thus warrants strict caution. By making us aware that things can go wrong at every turn, defensive pessimism is perfect in the sense that a lot of our current misery is directly a product of our seemingly proud all-knowing ego, and the cultural euphoria that everything would always eventually be alright.

It will take all sorts to make the desert ahead survivable in case you do actually get lost. However, the foresight of packing an extra bottle and anticipating the eventuality that water might run out seems better on face value than holding out to the hope that we will run into an oasis before the “half full” glass runs out. There’s no correct way to think about things that fit every situation and every person. You will have to find your own ways in the world. The real reason thinking positively can work well is because it motivates people to go out and make the change. If thinking positively leads you to productive action, that’s great. But it doesn’t for everyone. All this to say that we shouldn’t count the pessimists out. Optimism, as we’ve seen, can turn dangerously into self-delusion pretty quickly. Indulging in it too frequently might leave us with nothing to fight for.