On concept, perception and language

A note on Sternbergs technique and evolution of language through embeded cognition

Validity of Sternberg’s Additive factors method.

The Sternberg Task and Serialisation

-

The experiment entails memorization of a positive set, a list of items such as numbers or words.

-

The subject is then asked about a particular test item that may or may not have actually been present in the set, and is asked to respond “yes” or “no” accordingly.

-

The time taken for the subject to respond is recorded. This process is then repeated over several trials. What Sternberg found was that response time tended to increase with the size of the list. This provided evidence for Serial and Exhaustive Search Theory, which proposes that people will search every item in an array without stopping, even if the item was found.

Overarching consensus

-

This is the general underpinning of his additive factors method. This is a method that uses reaction time measured over a range of tasks in order to identify different cognitive processing stages. He argues that the indications for serial processing stages result either from a single processor switching from one to the next processing stage, or from one processor waiting for the output of another processor.

-

Serial processing models have been refuted in the past because they would not acknowledge parallel processes and feedback loops. Also, they would not account for tasks in which stimuli prime response movements in unintended ways (like Stroop task).

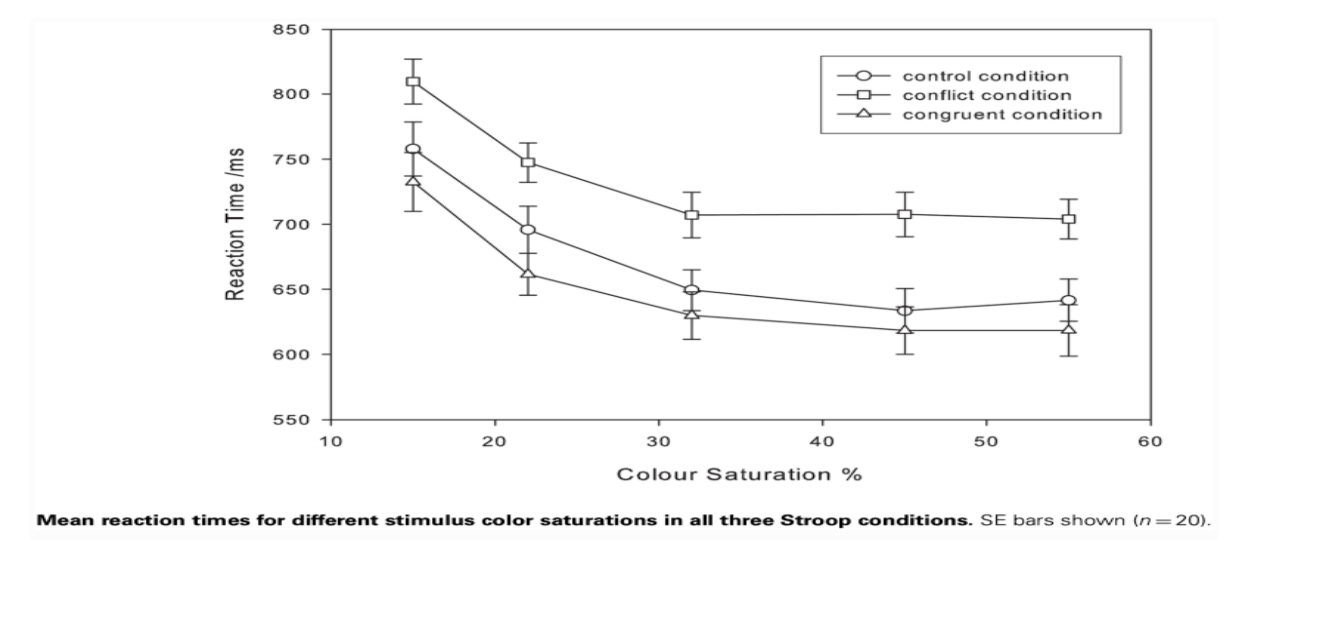

Hence, there have been studies that demonstrate additive factors can be successfully accounted for by existing single stage models of the Stroop effect. The Stroop task is ideal for this comparison because it uses both the perceptual representations (perceiving the colour of the word) and cognitive elements (representation,concept of the words and colours in our mind) to produce a correct response. Hence, if we can show that a discrete model is not necessary or can be accounted for by continuous processes, we essentially argue that a differentiation and demarcation of processing in the brain is not apparent.

Empirical results of the stroop task as below.

The Additive Factors Method

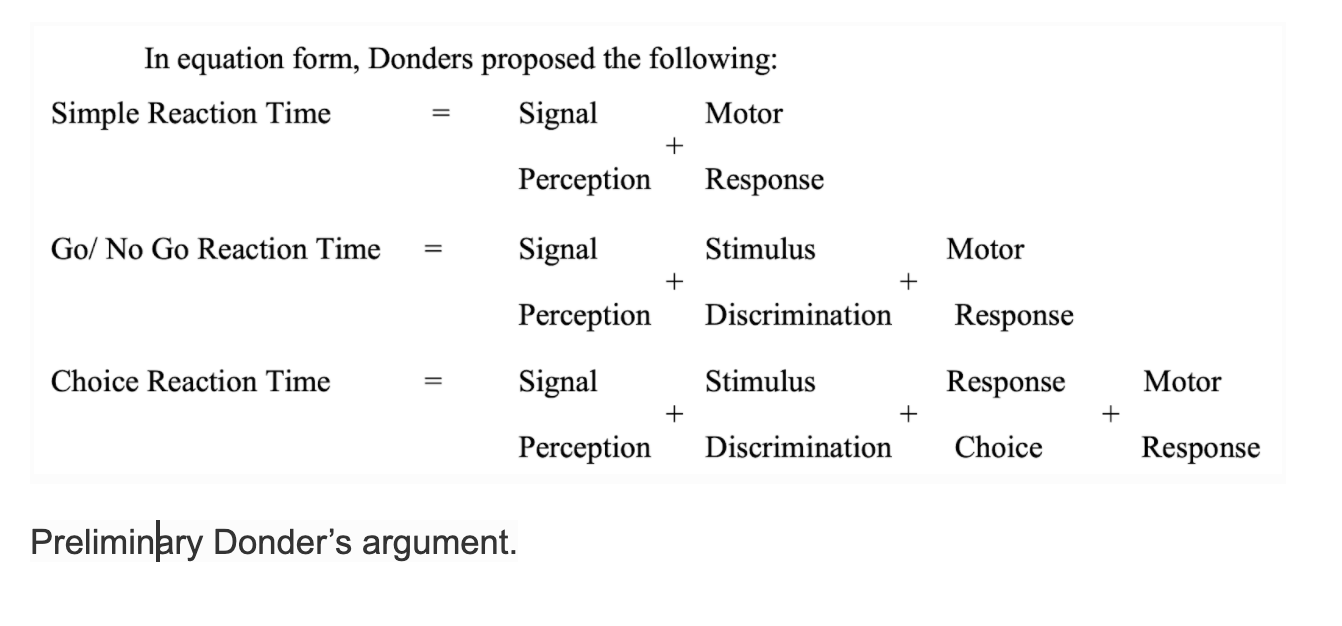

According to the assumptions of the AFM, independent components – “stages” – of decision making are revealed by the analysis of how different factors affect reaction times. Hence, if change in one factor affects Reaction Times independently of the change of another factor, then it is concluded that the two factors affect different stages of decision making.

Thus in this way, AFM provides a framework to assess the minimum number of independent processes (or steps) that are involved in decision making. This method has supported the independence of stimulus processing and response selection. However, the AFM method can only point to the algorithmic level of choice reactions, not the implementational level as described in Marr’s Tri-level approach.

The Additive Factors Method - Assumptions

-

Measuring a single small unit can be accomplished by measuring a large, known quantity of small units then dividing by the number of units. For example, to measure the thickness of a single sheet of paper with an ordinary ruler, measure the thickness of a stack of paper sheets, then divide by the number of sheets.

-

The total time to complete a response is literally the sum of the times of separate processing steps. Thus, if it takes 200 msec to complete visual decoding, 300 ms to complete scanning, and 500 ms to make a detectable response, the total time to respond is 200 + 300 + 500, or 1000 ms.

-

Some individual processing steps, such as pressing a response key, take the same amount of time regardless of the amount of information to be scanned. For example, if response execution takes 500 ms when scanning 1 item, it should only take 500 ms when scanning 4 items. The times for steps that stay the same can be treated as constants.

Basic Critique

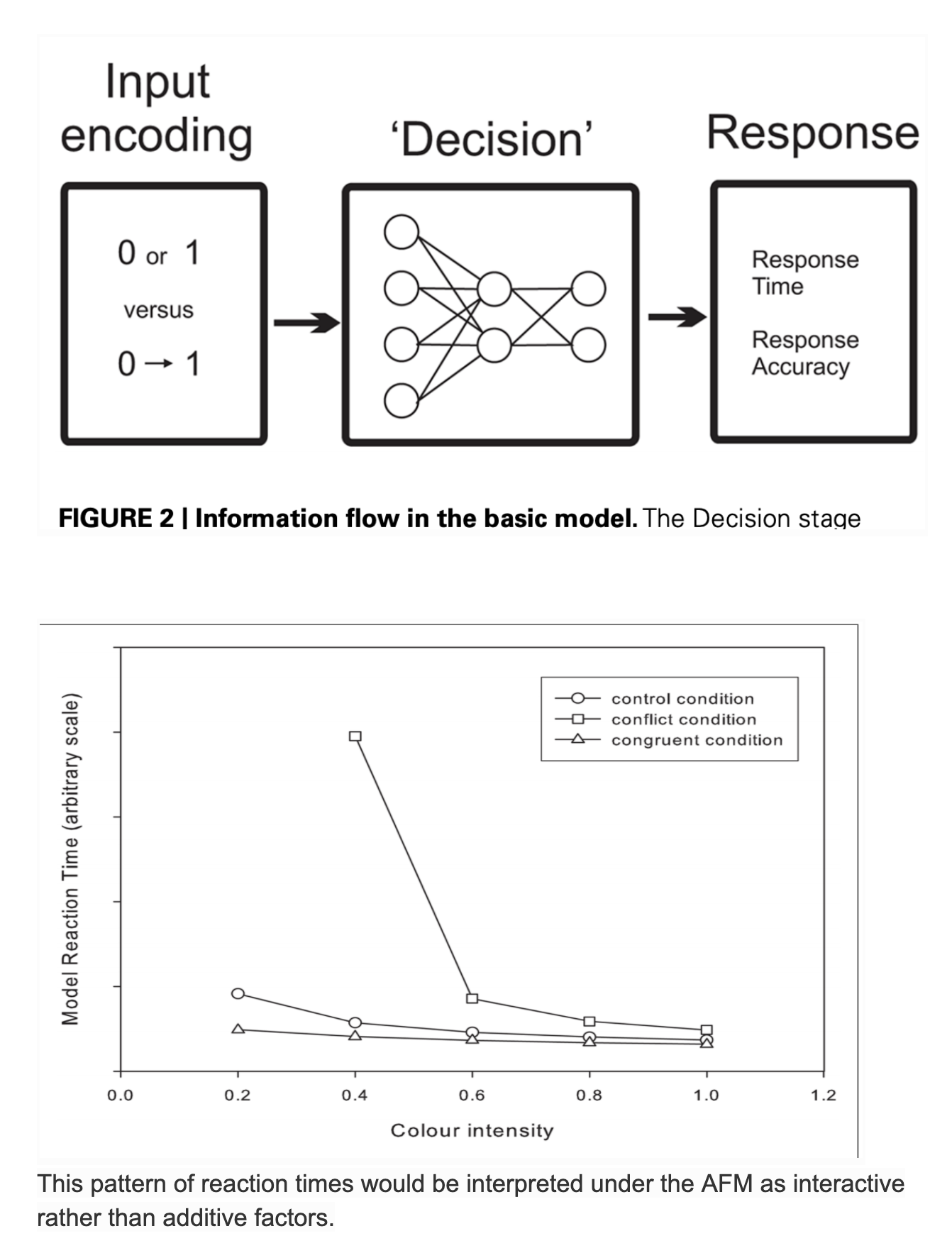

Thomas (2006) shows that AFM can predict interaction of factors once reasonable assumptions about the representation is taken into account. In contrast, Parallel Distributed Processing (PDP) framework suggests information being continuously available and interactively processed across multiple locations. McClelland (1979) showed that such a PDP “continuous processing” model could produce results which were consistent with the AFM, despite the lack of the discrete serial modules that the AFM is usually assumed to imply. Let us now, come back to the stroop task, compare and contrast the continuous with discrete models to comment on the serialization.

Continuous Stage Models - Cohen et al

The basic idea is that to activate an associated response code, a stimulus code needs to be translated into the response (As long as the primary response is not selected).

The essence of the model is that it evaluates using a distribution network, the word and color information in the stimulus and “responds based on the ink color, ignoring the word”. The weights of these factors and their combination, leads to the response, which signals the selected response. It does this after a certain amount of evidence, from all units in the model, has been accumulated. This model is a continuous processing model. Activity in all parts of the model is continuously updated as the effect of the change in inputs propagates. Although this may have many architectural stages, all components are running simultaneously and passing information without delay to each other.

Now for Stroop, In this model, the word and color information is represented by 0 or 1 values. The stimulus color, say, was red, the input unit for “red” would be restricted at 1 and the input unit for green would be restricted at 0. To simulate intermediate intensity, values between 0 and 1 were used. Both the color and the word input values were restricted at the same intermediate values, namely 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, or 1.0. This reflects the corresponding variation in the strength of the input representation with varying color saturation.

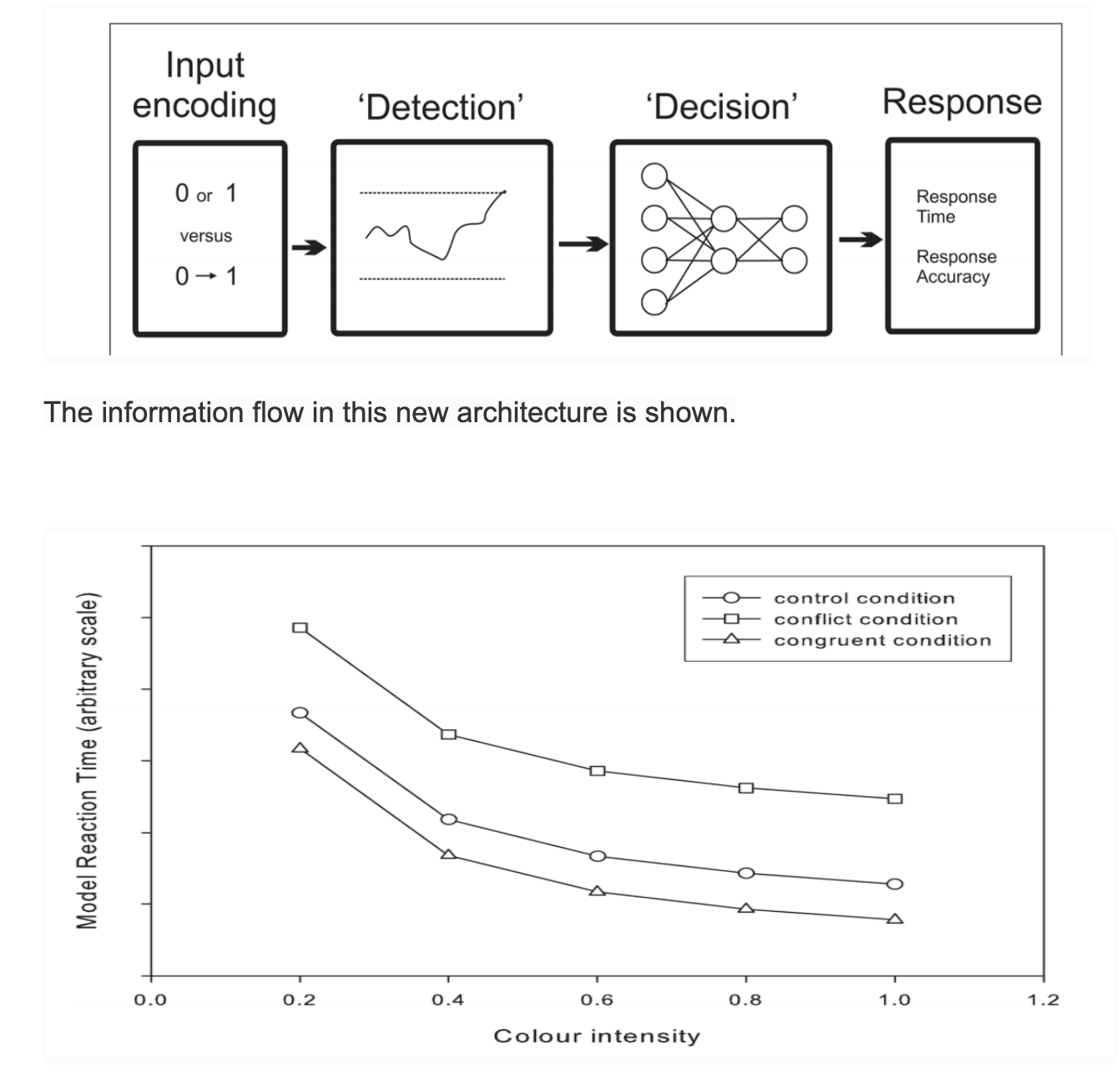

Discrete Stage Models - Two stage

A two stage, discrete processing variant of the Cohen model is constructed by adding a “detection” stage. This stage delays inputs to the second stage and until this output is passed, no other processing can take place. The influence of color saturation is incorporated by providing continuously valued inputs to the detection stage only.

The interference effect is larger than the facilitation effect across all stimulus intensity values, and that both effects are consistent across all stimulus intensity values. Note, however, that this is not logically sufficient to justify the inference of discrete stages from additive factors in the response times.

Note that in accordance with AFM, the stimulus intensity only affects processing in the first stage, and the Stroop condition only affects processing in the second stage.

Consequences for Decision Making

The essence is that single stage models of decision making will be useful at the data-descriptive level and for defining optimality, but multistage models will be required to account for experimental situations where decision making departs from optimality. The models presented here suggest that the simple decision making models developed to account for simple perceptual decisions cannot alone be a complete model of decision making. Without assumptions about other elements of perception and action selection, simple response mechanisms are insufficient to account for empirical data once the scope of decision making moves beyond the simple perception.

Functional vs Structuralist approach to Reaction Times

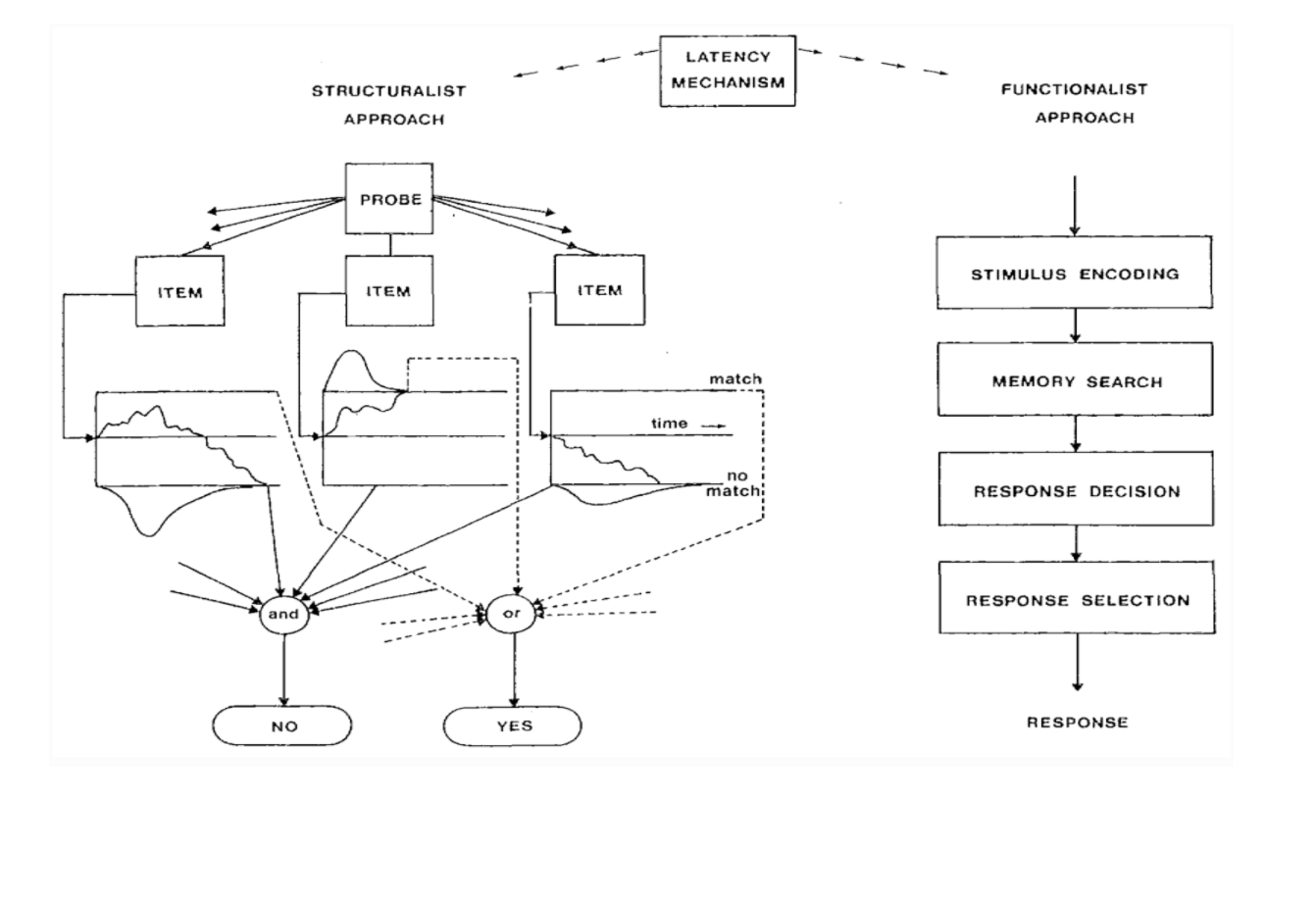

When an RT paradigm is used, the experimenter is usually interested in the mechanism that accounts for the time that passes between stimulus and response, commonly denoted by the term latency. It is assumed that this mechanism induces a characteristic, stationary probability distribution on RT. Globally, the various approaches to the decomposition of RT can be reduced to two major trends: the functionalist approach and the structuralist approach.

The functionalist approach to RT originates in its recent form from the work of Sternberg (1966, 1969). The reasoning behind Sternberg’s method is (a) that the stimulus-response process consists of a number of serial stages and (b) that different stages perform different functions. In a way, this approach takes its starting point at the level of studying the effects of various experimental conditions and from there seeks conclusions concerning the components of the stimulus-response process.

Originally Sternberg (1966, 1969) postulated four stages: stimulus encoding, information processing and evaluation, response decision, and response selection and evocation. Sanders (1980) already postulates six stages based on a review of the RT literature: stimulus preprocessing, feature extraction, identification, response choice, response,programming, and motor adjustment.

Ideally, a stage has the following four properties: (a) for a given input, the output is unaffected by factors influencing its duration; (b) a stage is a functional entity that is psychologically and qualitatively different from other stages; (c) one stage can process only one signal at a time; (d) stage durations are stochastically independent.

The main theoretical difference between the functionalist and the structuralist approach lies in the specification of the underlying stochastic mechanism. This mechanism is completely specified in the structuralist approach, whereas in the functionalist approach one only makes some general assumptions regarding the mean and variance of the response process. For this reason, the structuralist approach is also referred to as the model or distributional approach, and the functionalist approach is commonly referred to as stage analysis of RT. The structural approach starts from specific assumptions about the stochastic mechanisms involved and from there derives predictions concerning relevant aspects of the process. In general, the objective of research efforts should be to describe, to predict, and to explain the phenomena we deal with. The functionalist approach asks essentially: “Which variables have an effect, and do they interact?” whereas the structuralist or model approach asks: “What are the processes involved, and how do the variables affect these processes?”

Embodied Cognition and Evolution of Language

Historical Overview

How language conveys meaning remains an open question. The dominant approach is to treat language as a symbol manipulation system: Language conveys meaning by using abstract, amodal, and arbitrary symbols (i.e.words) combined by syntactic rules (e.g. Chomsky,1980; Fodor,2000; Pinker,1994). Words are abstract in that the same word, such as “chair” is used for big chairs and little chairs, words are amodal in that the same word is used when chairs are spoken about or written about, and words are arbitrarily related to their referents in that the phonemic and orthographic characteristics of a word bear no relationship to the physical or functional characteristics of the word’s referent.

A natural language is a structured symbolic system that involves a systematic mapping between a virtually unbounded set of thoughts and a virtually unbounded set of sounds or manual gestures. Given our limited cognitive abilities, it is common to explain linguistic competence in terms of a finite set of stored lexical units or complexes and combinatorial principles.

An alternative view is that linguistic meaning is grounded in bodily activity. Cognitive Linguistics has used the notion of embodiment to explain facts about language since its inception. There have been three distinct phases in the application of the idea of embodiment to empirical work on language and cognition.

The first was analytical in that it involved linguists − inspired by work in cognitive psychology − looking for evidence of how the conceptual resources that underlie language use might be embodied through analysis of language. Work in this stage produced results that did not speak much to mechanisms, and as a result were equally compatible with the developmental and online types of embodiment.

The second phase is the process phase, which involved refinement of the online version of embodiment in a way that has generated a new theoretical framework, and inspired a substantial body of empirical work.

And the third phase is the function phase, in which researchers are refining their tools in an effort to determine exactly what embodiment does for specific aspects of language use and other cognitive operations.

However, abstract concepts such as DEMOCRACY, ENTROPY, JUSTICE, NUMBER, and TRUTH are a critical issue for embodied cognition because it is difficult to see how they can be captured by representations grounded in sensorimotor systems. There have been notable attempts to address this problem, including appeals to metaphoric extension.

Metaphors - Could the future taste purple?

When producing speech, people usually generate an impressive amount of spontaneous gestures, bodily postures, and facial expressions. More precisely, people produce, in a perfectly synchronized manner spontaneous gestures which somehow match the meaning, timing, and form of the oral expressions used.

For instance, with a hand or a finger, people point towards something in their backs at the very moment when they say ‘all the way back in the thirties’. Or they show something in front of them when saying ‘the days ahead of us’. Therefore, bodily actions (i.e., spontaneous gestures) and speech, not only are coherent, but occur with an impressive synchronicity with speech.

It has been shown that an important amount of abstract thought is unconscious (i.e. it happens below the level of awareness and therefore is often beyond introspection), and it has shown that concepts are systematically organized through everyday cognitive mechanisms such as conceptual mappings. The most well known conceptual mappings are conceptual metaphors (Lakoff and Johnson, 1980).

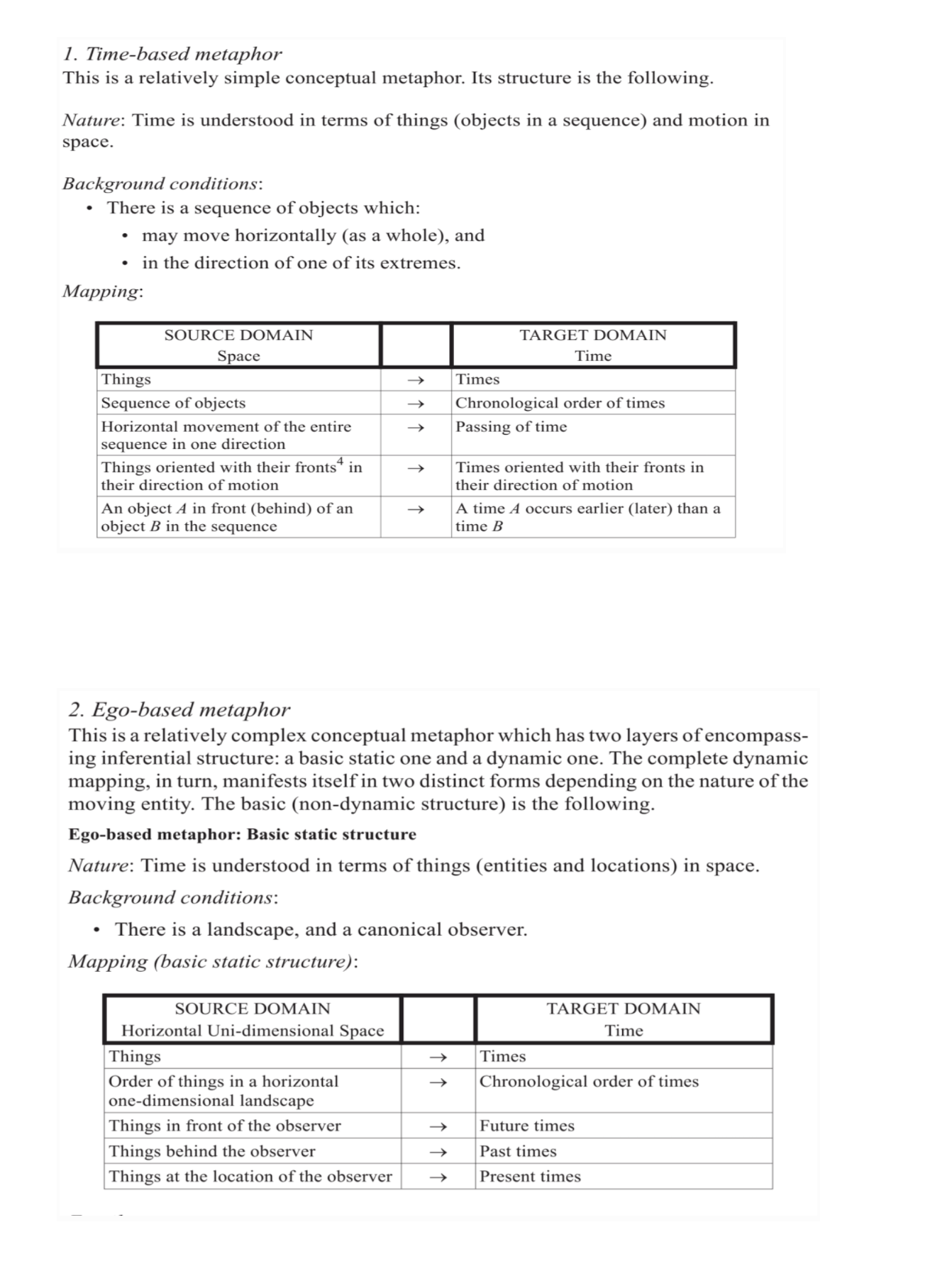

A conceptual metaphor is a cognitive mechanism that allows us to make precise inferences in one domain of experience (target domain) based on the inferences that hold in another domain (source domain). Through this mechanism, the target domain is understood, often unconsciously, in terms of the inferential structure that holds in the source domain. A conceptual metaphor, as understood in cognitive linguistics, does not belong to the realm of words but to the realm of thought. And this is very important to keep in mind: a conceptual metaphor is a cognitive mechanism, an inference-preserving cross-domain mapping. Particularly relevant is the distinction between time-based metaphors and ego-based metaphors.

The Blank Screen Paradigm

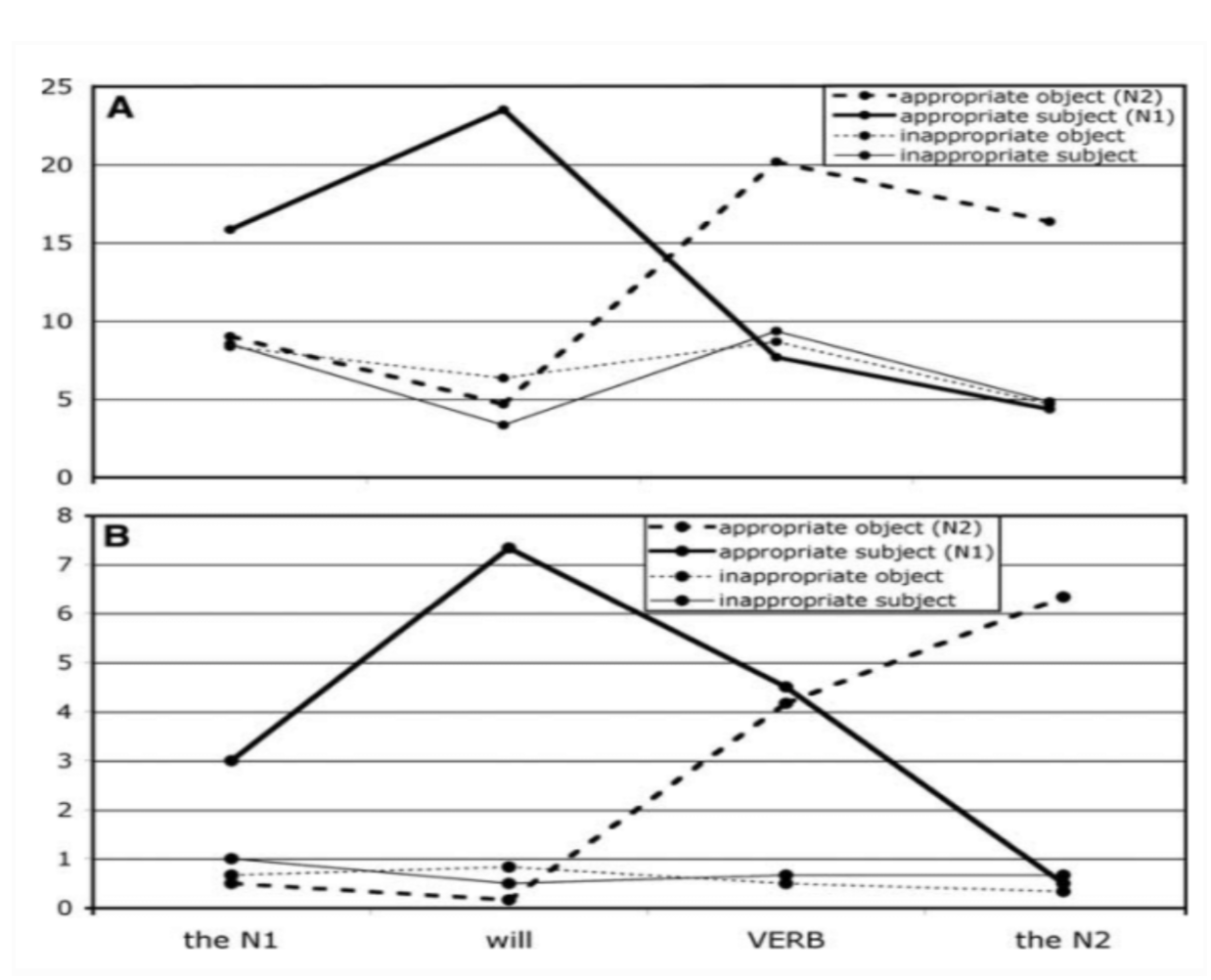

The ‘visual world paradigm’ typically involves presenting participants with a visual scene and recording eye movements as they either hear an instruction to manipulate objects in the scene or as they listen to a description of what may happen to those objects. In this study, participants heard each target sentence only after the corresponding visual scene had been displayed and then removed.

For a scene depicting a man, a woman, a cake, and a newspaper, the eyes were subsequently directed, during ‘eat’ in ‘the man will eat the cake’, towards where the cake had previously been located even though the screen had been blank for over 2 s. The rapidity of these movements mirrored the anticipatory eye movements observed in previous studies. Thus, anticipatory eye movements are not dependent on a concurrent visual scene, but are dependent on a mental record of the scene that is independent of whether the visual scene is still present.

Why did the eyes move to a particular location when there was nothing there? One possibility is based on the idea that very little information about one part of a visual scene is maintained internally when the eyes move to another part. Richardson and Spivey (2000) proposed, following O’Regan (1992), that the visual system instead uses the scene itself as an external memory, using oculomotor coordinates (defined relative to the configuration of cues within the scene) as pointers towards this external memory. The activation of these pointers causes the eyes to move to the corresponding coordinate from where information about the contents of that part of the scene can be retrieved.

In conclusion: Eye movements that are triggered during linguistic expressions are not contingent on an item being co-present with that expression. Thus, even when the visual scene is concurrent with a linguistic expression that refers to an item within that scene, information about where to move the eyes in order to fixate that item may be based not on the actual location of that item within the scene, but on the location of that item as represented within a mental representation of the scene.

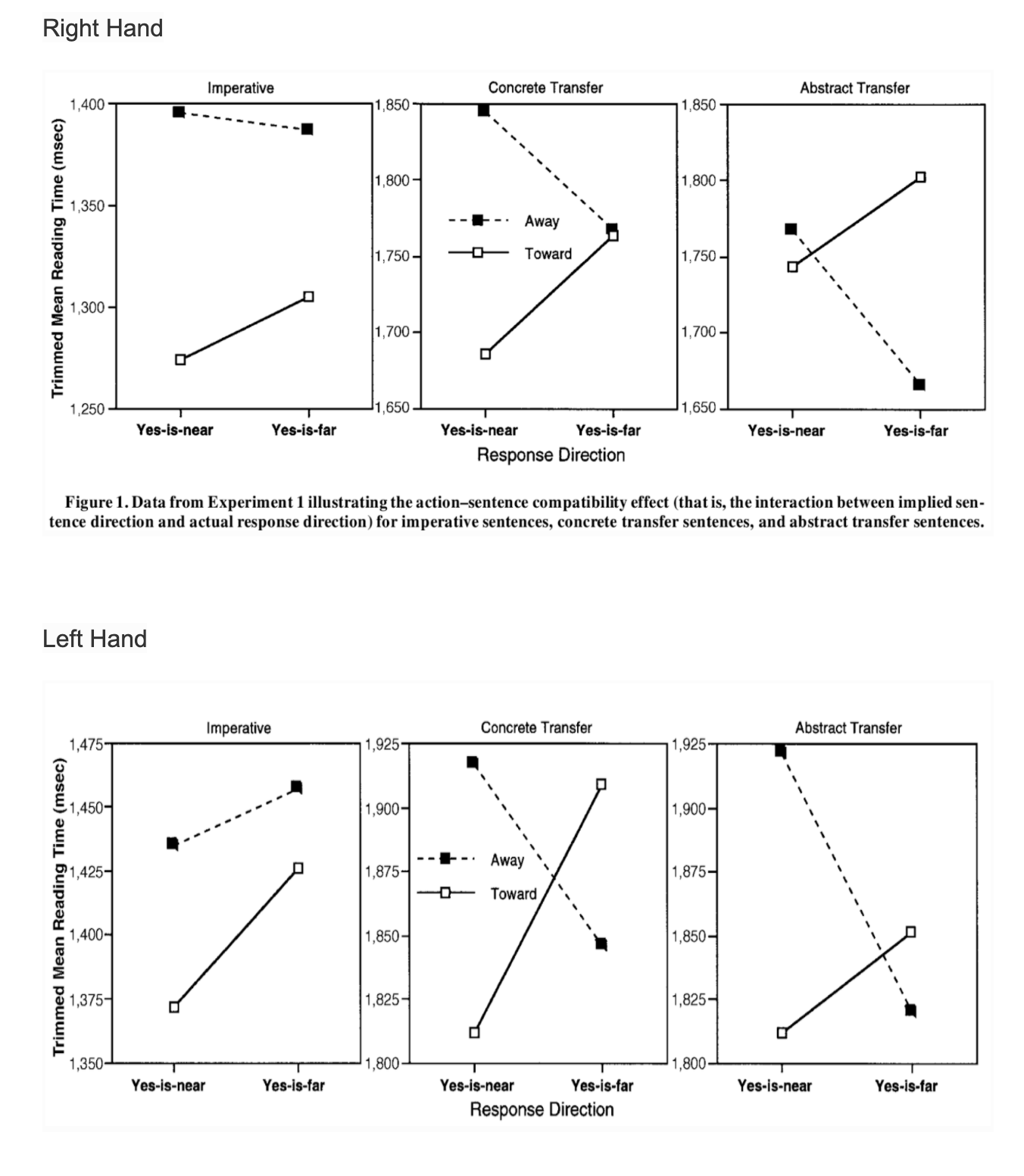

Grounding Action in Language - Glenberg

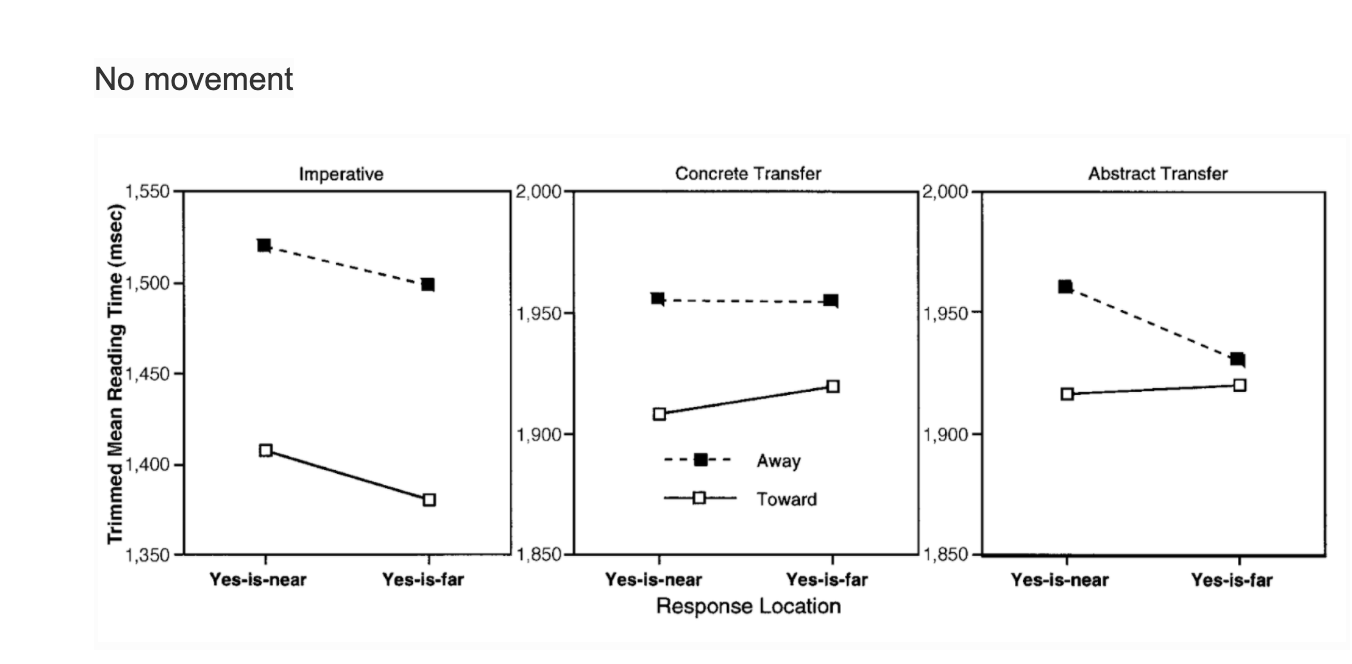

This demonstrates that merely comprehending a sentence that implies action in one direction (e.g.,“Close the drawer” implies action away from the body) interferes with real action in the opposite direction (e.g., movement toward the body). These data are consistent with the claim that language comprehension is grounded in bodily action, and they are inconsistent with abstract symbol theories of meaning.

Experiment :-

Participants were presented with a series of sensible and nonsense sentences, and they were asked to determine as quickly as possible whether each sentence made sense. One independent variable, implied sentence direction (toward/away), was manipulated for the sensible sentences. Thus, toward sentences, such as “Open the drawer” and “Put your finger under your nose”, implied action toward the body. A way sentences, such as “Close the drawer” and “Put your finger under the faucet,” implied action away from the body.

The nonsense sentences, such as “Boil the air,” did not seem to imply any direction. Note that the participants were never instructed to consider the implied direction; their task was merely to judge sensibility. The actual response direction (yes-is-near/ yes-is-far) was manipulated by using a specially constructed button box.

According to the study, meaning is action-based: Understanding a toward sentence requires meshing affordances (e.g., of a drawer and the action of opening), resulting in a simulation of actions toward the body, whereas understanding an away sentence results in a simulation of actions moving away from the body. If this simulation requires the same neural systems as the planning and guidance of real action, understanding a toward sentence should interfere with making a movement away from the body to indicate yes (yes-is-far), and vice-versa. This is called the Action Congruency Effect.

Half of the 80 sensible sentence pairs (toward/away pairs) were in the imperative, such as the examples above. The other half of the sensible sentence pairs described a type of transfer. The concrete transfer pairs described a physical transfer. Half of these used the double-object construction (e.g., “Courtney handed you the notebook/ You handed Courtney the notebook”), and half used the dative form (e.g., “Andy delivered the pizza to you/ You delivered the pizza to Andy”). The 20 abstract transfer pairs described a nonphysical transfer, such as “Liz told you the story/ You told Liz the story” and “The policeman radioed the message to you/You radioed the message to the policeman.”

Inseparability Principle/SLA - Atkinson

Three SLA principles based on extended, embodied cognition:

- The Inseparability Principle: Mind, body, and world work together in learning/SLA;

- The Learning-is-adaptive Principle: Learning/SLA facilitates survival and prosperity in complex environments; and

- The Alignment Principle: A major engine of learning/SLA is alignment, the means by which we effect interaction.

The Inseparability Principle and SLA

Consider four questions vis-a-vis the picture below,

- Who is the person in the picture?

- What is she doing?

- Where and when?

- Why?

The aim of this exercise is to suggest that SLA is more than just a cognitive input/restructuring/output process, and what some of that ‘more’ may be.

This pictorial illustration has three implications for SLA. First, it suggests that people cognize/learn not just mentally, but in environments composed of bodies, cognitive tools, social practices, and environmental features. If, as the inseparability principle argues, such contexts crucially affect cognition/learning, then they cannot be treated as optional extras. Regarding learning this suggests that:

- Learning is more discovering how to align with the world than extracting knowledge from it (Ingold 2000); and

- By being environmentally embedded, knowledge/cognition is made public and thereby learnable.

The second implication of this illustration concerns the quality of cognition/learning (van Lier 2002). The personal relationships learning involves, its role in identity construction (Norton 2000), where and under whose sponsorship it occurs, and how it is embodied and enacted fundamentally influence its outcome. Unlike computers, humans don’t just process—they find value and meaning. This affects learners’ engagement with learning opportunities, including whether they engage at all.

Third, if cognition/learning is complex and multimodal, as the illustration suggests, then it must be studied complexly and multimodally.

The learning-is-adaptive principle and SLA

The learning-is-adaptive principle has four linked implications for learning/SLA:

- Learning/SLA is relational: Learning-as-adaptive-behavior concerns how to relate—how to articulate with one’s environment.

- Learning/SLA is experiential, participatory, and guided: One learns to relate by relating - learning is experiential.

- Learning/SLA is public: One crucial way learning is guided is by externalizing its object while focusing the learner’s attention (Schmidt 2001) on it.

- Learning/SLA is aligning, and learning to align: This final point summarizes the preceding three: Learning is a process of alignment—of continuously and progressively fitting oneself to one’s environment, often with the help of guides.

The alignment principle and SLA

First, it means having formidable pre-existing capacities for interacting without necessarily sharing a language. That is, all language learners have powerful interaction engines supporting their learning at every turn.

Second, SLA itself is a process of alignment—of learning the ‘differences that make a difference’ (Bateson 1972: 459) in the L2 environment. This is what our guides teach us as we engage with the environment: A requisite idiom or formula here, a form-function relationship there—to do that, you need to say this. By trying to align with our environment—by learning to behave in eco socially adaptive ways—we become ‘enskilled’ (Ingold 2000: 5).

Third, as noted above, alignment has a public face: Our aligning/learning behaviors extend into the world, and as our guides facilitate and respond to them, alignment is further externalized. Ultimately, sociocognitive approaches to SLA are based on this tripartite premise: (i) Mind, body, and world are in continuous processes of interactive alignment; (ii) These processes are partly public; and (iii) In being public, they are learnable. Thus, if cognition is the site of learning, it is extended, embodied cognition that makes learning possible, at least in part.